I remember clearly the first time I managed to understand a poem in classical Chinese. It was like seeing someone perform an unexpected conjuring trick, shaking out a piece of rope and then tossing it up into the air to make it stand stiffly like a stick . Then back again.

I remember clearly the first time I managed to understand a poem in classical Chinese. It was like seeing someone perform an unexpected conjuring trick, shaking out a piece of rope and then tossing it up into the air to make it stand stiffly like a stick . Then back again.

There was certainly some kind of alternation between states which I couldn’t quite understand. How could twenty simple syllables also produce some kind of shimmering complexity. Where was this chemical reaction taking place?

Another way I think of these poems is as of magic seeds. Hold them in your hands and you see a whole tree, press them tight and they are simple seeds again.

All poetry has an effect of incantation. This is why (like music, and unlike prose) the spell becomes stronger every time you repeat it. But it is an effect which seems to me to be particularly strong in classical Chinese poetry, perhaps because those syllables all have weight and length. It really does seem like you have to read them out all with equal power to make the magic work and open up the poem’s door.

When you try and translate one of these poems into English you have to add in all the unstressed syllables and unweighted words which we use and the result is that you water the poem down to an unrecognisable degree. Try and drag out its meanings and it is like taking a watch to pieces. It doesn’t tick. Try and portray its shape and you end up with something like a stuffed bird. Something stiff which can no longer fly. Most translations of Chinese poetry are like that.

A few people have produced wonderful poems in English by attempting to translate from the Chinese. One such case is Ezra Pound. To quote an outstanding translator of poetry, Elliot Weinberger, these poems were “written by an American who knew no Chinese, working from the notes of an American (Ernest Fenollosa) who knew no Chinese, who was taking dictation from Japanese simultaneous intepreters who were translating the comments of Japanese professors”. Pound actually thought the name of the poet he was translating was “Rihaku”, which is the Japanese rendering of Li Bai (or Li Po), generally considered China’s greatest poet, together with Du Fu (or Tu Fu). And yet despite all his misunderstandings and the Japanese-sounding place names he comes up with, Pound not only produces some beautiful poems but actually manages to sound like Li Bai:

The River-Merchant’s Wife

While my hair was still cut straight across my forehead

I played about the front gate, pulling flowers.

You came by on bamboo stilts, playing horse,

You walked about my seat, playing with blue plums.

And we went on living in the village of Chokan:

Two small people, without dislike or suspicion.

At fourteen I married My Lord you.

I never laughed, being bashful.

Lowering my head, I looked at the wall.

Called to, a thousand times, I never looked back.

At fifteen I stopped scowling,

I desired my dust to be mingled with yours

Forever and forever and forever.

Why should I climb the look out?

At sixteen you departed,

You went into far Ku-to-en, by the river of swirling eddies,

And you have been gone five months.

The monkeys make sorrowful noise overhead.

You dragged your feet when you went out.

By the gate now, the moss is grown, the different mosses,

Too deep to clear them away!

The leaves fall early this autumn, in wind.

The paired butterflies are already yellow with August

Over the grass in the West garden;

They hurt me. I grow older.

If you are coming down through the narrows of the river Kiang

Please let me know beforehand,

And I will come out to meet you

As far as Cho-fu-Sa.

Another translator who has produced some beautiful modern English poems from the Chinese is David Hinton. Here is one based on a poem by Du Fu which I like a lot.

Full Moon

Above the tower — a lone, twice-sized moon.

On the cold river passing night-filled homes,

It scatters restless gold across the waves.

On mats, it shines richer than silken gauze.

Empty peaks, silence: among sparse stars,

Not yet flawed, it drifts. Pine and cinnamon

Spreading in my old garden . . . All light,

All ten thousand miles at once in its light!

These are both wonderful achievements but they still don’t show you the insides of a Chinese poem. I think that you can get an idea of that in a wonderful book I came across by chance in a bookshop in New York many years ago, thanks to the fact that I still haven’t learnt to tie up my shoe-laces properly. It was behind a door about six inches from the floor and if I hadn’t been looking for the most out-of-the-way place to get down on one knee and make a better knot I would probably never have read it. The book is “The Heart of Chinese Poetry” by Greg Whincup.

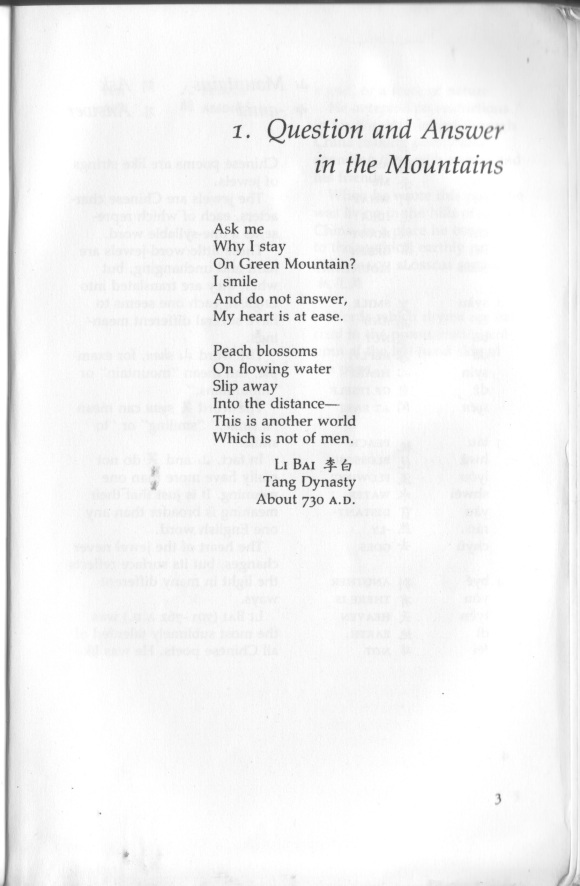

What Whincup does in this book is provide a standard English translation, together with a phonetic rendering, the Chinese characters, a word-for-word translation and an illuminating explanation, not just of the poems, but of the lives of the poets, the history of China and how the language works. Here are a few examples. This is the very first poem he includes (click to enlarge the pages):

And here, to restore the balance between Li Bai and Du Fu, is one by Du Fu:

Whincup uses the Yale system of transliteration, which may seem a little strange, now that Pinyin is so widely used, but it doesn’t take long to get used to it.

I know of some other excellent books which use a similar approach to explain Chinese poetry, for example Wai Lim Yip’s Chinese Poetry and François Cheng’s L’écriture poétique chinoise, but they can seem a little intimidating to people who know nothing about Chinese. I always give people Whincup’s book as an introduction to Li Po, Du Fu, Meng Hao Ran, Wang Wei, Su Shi, Du Mu, Tao Qian, Jia Dao and all the other wonderful poets I would have liked to show examples of. Whincup’s book looks slim and looks simple. It seems to say “Let me show you this little garden” and then it leads you through a forest.

Beautiful, Philip! Please do show the other examples.

Grazie per avvicinarmi a queste bellissime poesie e a due sensibilissimi poeti. Così lontani in termini di chilometri eppure vicinissimi alle corde dell’anima